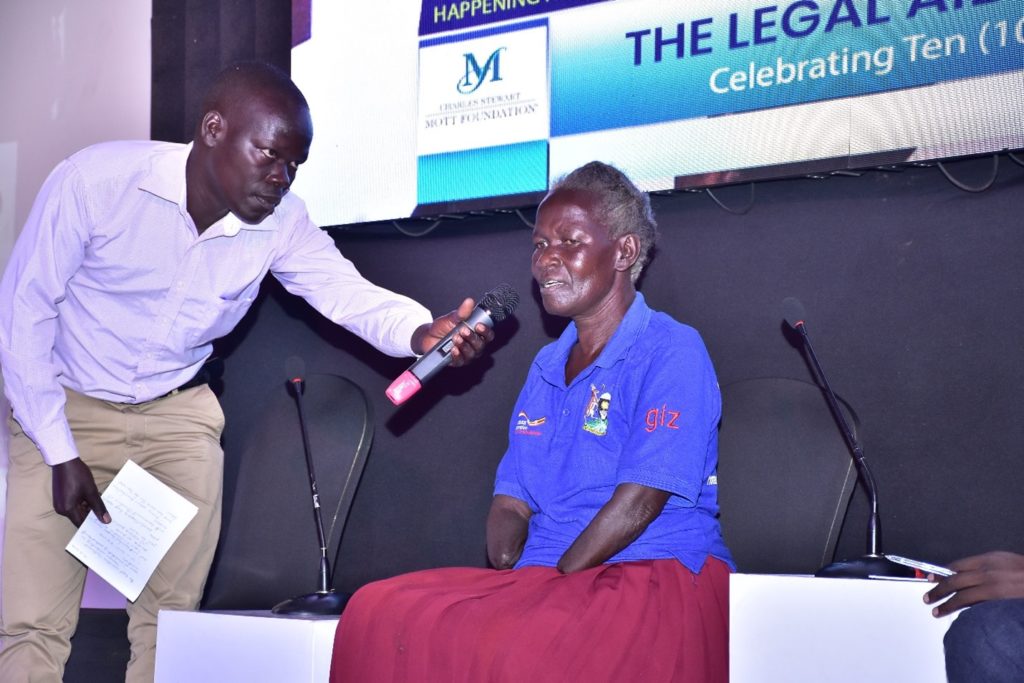

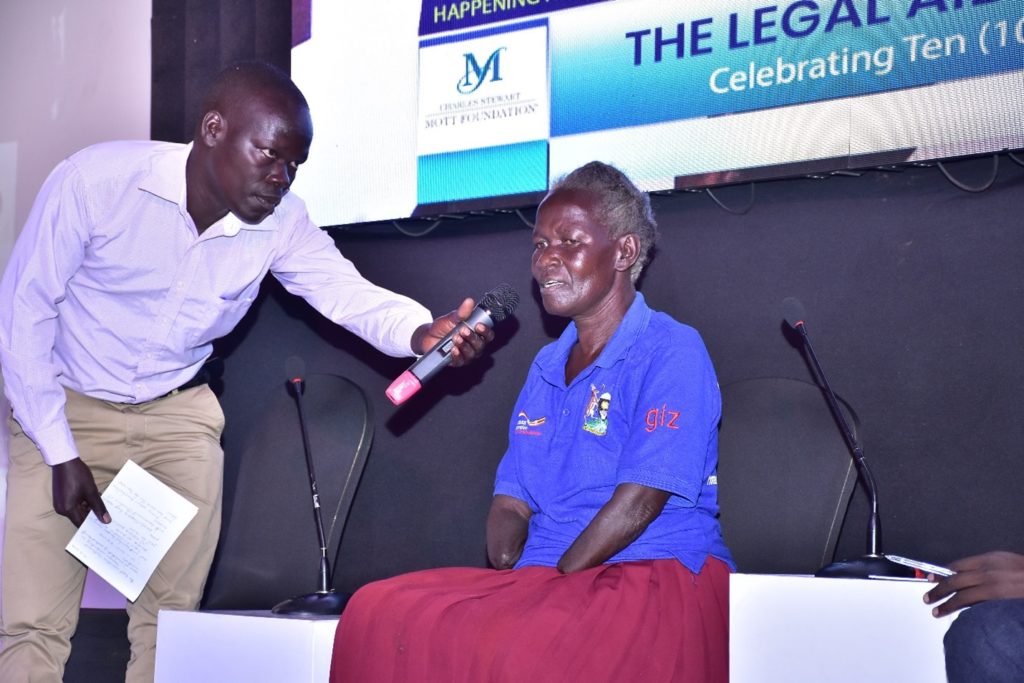

1 Pasculina Oming and her son, Steven Oming

“As we delve into the discussions and sessions today, let us not only celebrate our achievements but also reflect on the challenges that lie ahead. The legal landscape is ever evolving, and our commitment to justice demands continuous adaptation and innovation. Together, we can shape a future where legal empowerment knows no boundaries and where the pursuit of justice is an inherent part of the human experience,”

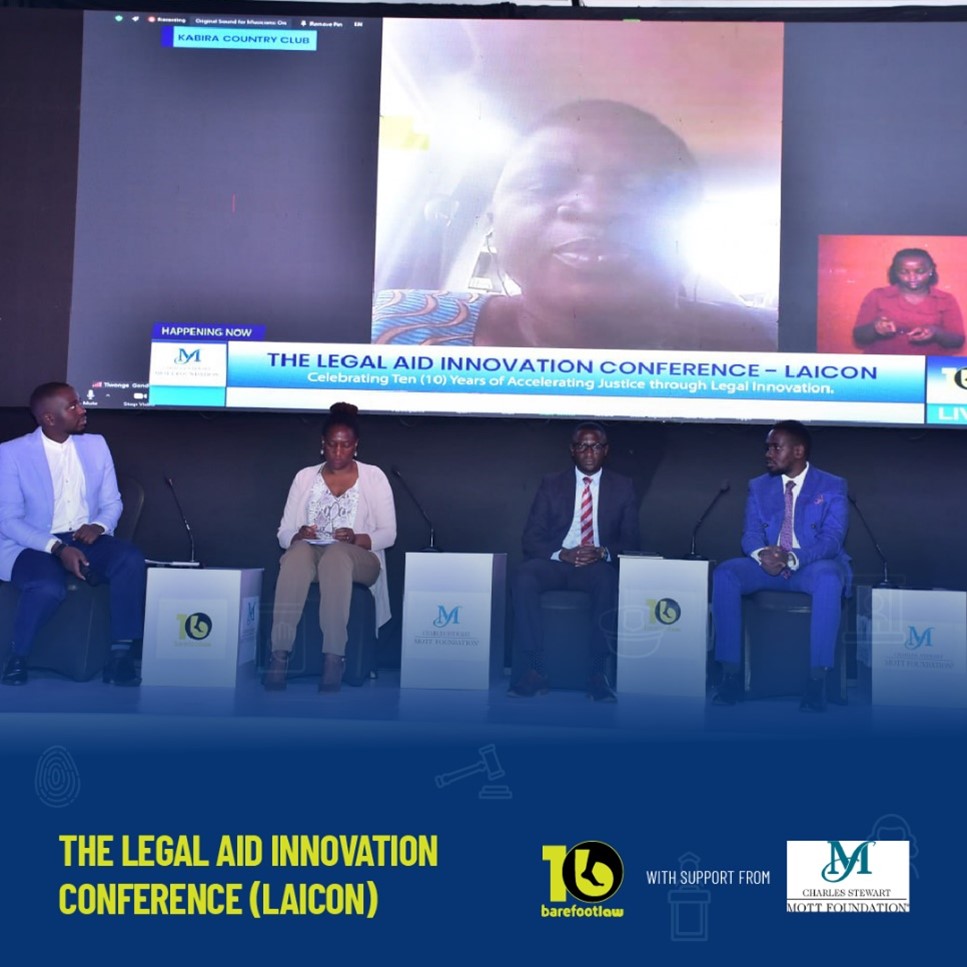

These were the opening remarks from Gerald Abila, the Founder and Executive Director of BarefootLaw, at the annual Legal Aid Innovation Conference (LAICON) that happened on Tuesday, 12th December, 2023 at Kabira Country Club.

It was a two-day event that culminated in the BFL@10 Gala on Wednesday, 13th December 2023. This year’s theme was “Celebrating a Decade of Accelerating Justice through Legal Innovation. What Next?” The conference goal was to bring together new and old justice innovators to reflect on their impact and deliberate on the future of justice in Africa. For the first time since its inception in 2017, LAICON explored justice innovations and practices in other countries besides Uganda, that is, Kenya and Malawi.

The event consisted of four panel discussions including two with people who have benefitted from BarefootLaw’s services over the past ten years, justice innovators from Kenya, Uganda and Malawi, and institutions of Justice in Uganda. The discussions centred around the panellists different innovations and the how they hope to fill the gap within the justice system in their respective countries with their innovations.

The Justice Innovation Landscape in Uganda, Malawi and Kenya[GL2]

4 Tiwonge Gondwe the Founder of Chikulamayembe Women Forum in Rumphi, Malawi.

The event started off with a panel discussing the innovation landscape for grassroots justice service providers in three countries across Eastern and Southern Africa. The panel was moderated by Timothy Kakuru, Director for Programs and Impact of BarefootLaw and the lead for the research project entitled “Approaches and Innovations in the Provision of Legal Services in Uganda, Kenya and Malawi.” The panellists were all innovators in Justice who have done phenomenal work that contributes to the access to justice environment of Uganda Malawi and Kenya and the discussion ranged around what they do, how they innovate and what they hope to accomplish in the future.

Ms. Marjorie Seruwo, the Executive Director, represented Concern for Girl Child (CGC). It’s an organisation that operates safe spaces for women and girls across the country. The organisation started off doing lobbying work for the rights of women and girls at the local level for things like education for the girlchild, prevention of child marriage and early pregnancy and advocating for equal treatment of girls and boys. After realizing that despite the sensitisation and advocacy, community and cultural leaders defaulted to their traditional treatment of girls, their perceptions not fully altered. Marjorie explained that in order to deal with the continuing harm to girls during the Covid-19 pandemic, CGC came up with Safe Spaces where girls could go for help, training and an environment where they could express themselves, their wants and aspirations. Through the vehicle of safe spaces, the girls are also able to challenge traditional norms and communicate to the community leaders without fear of reprisals.

Chikulamayembe Women’s Forum, a Malawi based organisation was represented by its Executive Director Tiwonge Gondwe. It is a grassroots women’s rights organisation which was started in 2007 and advocates for women’s rights, access to justice and works to resolve land issues that women in the communities they serve face. Similar to CGC, Tiwonge emphasised the historical prejudices against girls and women as the driving force behind the oppression they face.

Jural media and Simply Legal were represented by their team leaders, Blair Atwebembere and Terry Kahuma respectively, both working in the media and legal information space. Where Jural media was created to be an online media house specialising in justice, law and order content, Simply Legal is a social media-based effort created to make legal information easier to understand. Both innovations were started to improve the state of legal information available to the public, with Mr Blaire emphasising the poor levels of understanding the media have portrayed when reporting on legal matters. The panellists had a rich discussion on what their motivations are and the environment within which they operate, expounding on the challenges they face.

From Kenya, appearing remotely, Assumpta Ndami gave talked in detail about the Dispute Resolution Hub which does a lot of dispute resolution with pro bono mediations done exclusively online. It was started in 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic when legal help for many seemed nowhere to be seen.

The panellists explored the motivations behind the innovations they have come up with, breaking down the need they saw, the fact that there was no better solution being presented and the leap they took to provide a solution to it.

The panel was concluded with each member talking about their desires for their innovation’s future, with all of them being optimistic about further growth of their work, serving more people and being put in a position to do better work for their communities. Many similarities in the laws, cultures and challenges that face the three countries were established and there was a strong sense of the struggle being shared by the panellists across borders.

Innovation in the Delivery of Justice[GL3]

5(L-R) Esther Akullu-Parliament of Uganda, Moses Okwalinga-ULS, Edgar Kuhimbisa-JLOS, Muleterwa Anatoli-Commissioner Community Policing, Grace Atim-Gulu University, Diana Doris Akide-Uganda Law Reform Commission, Peninah Igaga & Alinda Shivan (screen)-BFL

One of the items on the agenda was a stellar panel discussion with innovators from justice institutions in Uganda. This panel saw representatives from institutions like the Justice Law and Order Sector, Uganda Police, Gulu University, The Parliament of Uganda, The Uganda Law Reform Commission, Uganda Law Society and BarefootLaw share their contributions to delivery of justice in Uganda.

The panellists shared insights into how their organisations are innovating for access to justice. Uganda Law Society highlighted their transition to use of online services including membership of the society. The Police shared that they launched an online complaint system, and a police app that allows the public to connect and communicate with the police at the tip of their fingers. The Law Reform Commission noted the introduction of braille for laws to ease access to justice for persons with disabilities. JLOS pledged to continue their financial and technical support to all the institutions of justice. Finally, BarefootLaw shared information about innovating for people that cannot access digital platforms. They mentioned that the model allows for the organization to conduct physical outreaches to serve people in the communities. A highlight was the mention of the BarefootLaw Law Box which is a mobile office where people in communities can go and be connected to a law digitally.

The panel was insightful and reflected on the challenges in innovation but were hopeful that these can be addressed for the greater good of ensuring access to justice for all.

User POV – Innovation from the eyes of the receiver[GL4]

6 R-L, Steven Oming, Pasculina Oming, Isaac Otim, Kennedy Kasozi, Kobusingye Winnie

Often when organisations plan seminars, webinars, and conferences, the people who receive and experience their services do not make it to the room. LAICON’2023 broke that cycle by holding two panels with the users of the justice services. These panels were the most captivating part of the conference because they highlighted real-life experiences of the injustices people face and acted as a mirror for all the justice actors present to see the impact and gaps in the services they provide.

Moderated by Isaac Otim, BarefootLaw’s Director of Legal Services, the discussion took a different approach as it offered a 360-degree testimonial from the people who received the legal help, and the lawyers that supported it. On stage was Pasculina Oming, Winnie Kobusingye, John Kennedy Kasozi (also a Lawyer at BarefootLaw) and Steven Oming (Pasculina’s son).

Pasculina was first introduced to BarefootLaw in 2015 after her late husband’s brother attacked her and cut off her arms after a land boundary dispute. BarefootLaw stepped in, took on the case, and saw it to completion until the perpetrator was charged for his crimes. Pasculina expressed her sincere gratitude to BarefootLaw, who went the extra mile and supported her throughout the years. Winnie Kobusingye was one of the first people that BarefootLaw served. She came to BarefootLaw in 2014 after the death of her husband who succumbed to a road accident leaving her helpless with three children (one being a newborn at the time). After being shunned away by her father-in-law, with guidance from her Local Council Chairman, Kasim, she turned to BarefootLaw who has supported her in more ways than one. She is also the inspiration for our Artificial Intelligence’s (AI) name “Winnie.”

The final panel discussion of the day was moderated by Joel Rubangapewany, a lawyer at BarefootLaw. It consisted of women that BarefootLaw has served at the BarefootLaw Box in Bala Sub County in Kole district. The panel comprised of Janet Akello, Sarah Amongi and Selly Akao, all who were able to resolve their legal needs.

Presentation of Preliminary Research Findings

7Lead Researcher for the “Approaches and Innovations in the Provision of Legal Services in Uganda, Kenya and Malawi” project Ruth Kigozi presenting the preliminary results of the research project in all 3 countries.

Lead Researcher for the “Approaches and Innovations in the Provision of Legal Services in Uganda, Kenya and Malawi” project Ruth Kigozi presented the preliminary results of the research project in all 3 countries.

The project objectives included identifying innovative practices in access to justice in Uganda, Kenya and Malawi, learning the improved results that those innovations present different from the traditional justice provision methods and working to figure out whether these innovative methods can be shared with other justice providers in order to help improve the access to justice environment in the focus countries.

At the onset, the team had challenges with finding innovations as there was a fear that only what was already in the sphere of influence of the innovators would be identified and the different types of innovations available might not be included. With this in mind, the researchers decided to pass on the role of identifying innovative practices to the public through crowdsourcing methods. Crowdsourcing would also enable the public to get involved in the project at the broader level of enabling the innovators to get an understanding of what is considered an effective grassroots practitioner and how they got to that position in the eyes of the people they have served.

The innovators nominated through the crowdsourcing process would then be vetted by a committee of experts brought together by BarefootLaw in order to identify who among the nominated innovators can be considered most impactful with their innovation, and that shortlist of innovators then being taken to the public to vote on who they considered most innovative.

Innovation in this study was defined as a process, a domain, a product, or service renewed and/or brought up to date by applying new processes, introducing new techniques or business models or establishing successful ideas to improve access to justice. Voting was done using Twitter (now X), Facebook and SMS.

Key Informant Interviews were thereafter also conducted with the heads of key stakeholders and leading legal service providers to gather qualitative information about legal innovations in the country. This information was supplemented by community surveys.

In Uganda, of the 40 innovators nominated by the public, 6 were voted on, with a total of 1,860 votes being received. The top three innovators were Centre for Technology Dispute Resolution (795 votes); Concern for the Girl Child (485 votes); Kumam Youth Development Group (220 votes).

In Kenya there were 42 innovators nominated by the public, and 6 were voted on. There was a total of 10,799 votes cast. Nyando Social Justice (3,948); Kisumu Mediation Centre (2,908); and Dispute Resolution Hub (1,871) got the highest votes.

In Malawi there were 21 innovators nominated by the public, and 4 were voted on. There was a total of 2,321 votes cast. Hub 22 (938 votes); Chikulamayembe Women Forum (787 votes) and Youth Response for Social Change (501 votes) were the winners.

By the time of the conference, the survey results for Uganda and Malawi were available, and Kenya was still ongoing. The results revealed the similarities and differences in the perceptions to justice between Uganda and Malawi with Malawians showing greater optimism for the justice sector and its potential than Ugandans. For example, 53% of the respondents in Malawi thought it was easy to access justice while only 29% in Uganda did. In general, the respondents from both countries agreed that their governments and nonprofits are working toward improving access to justice (52% in Uganda and 50% in Malawi).

The respondents did not think that either the governments of Malawi or Uganda have done much to improve access to justice using technology, with none of the questions asked gaining more than 26% positive responses, whether it be using mass media to sensitize through radio/ tv, the use of phone services to report cases, the use of technology to follow up cases or make online rulings. According to the citizens of these countries therefore, a lot more can be done with technology to improve access to justice.

The survey and the crowdsourcing activities revealed that the public is very optimistic for the role that innovations, especially technological in nature, can play to improve access to justice for the marginalised. Respondents to the survey recommended that governments continuing to open up the NGO space, addressing corruption and strengthening the capacity of local justice providers would play a big role in improving access to justice in the project countries.